Siddhartha

all things end

I read Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse during my senior year of high school. The entire year was virtual because of COVID, so I learned almost nothing and ended the year having barely scraped a B in half my classes.

That year, death was always on my mind. I lived for a few months with my friend Josiah, who was a devout Christian along with the rest of his family. I was not a devout Christian. I didn’t know what I was, because every time I thought about religion, I thought about death, and it terrified me.

I talked with different people about this, but no one seemed to understand how I felt. My Christian friends did not fear death or worry about it because they had the afterlife covered already. My atheist friends seemed to have accepted the onslaught of oblivion as their fate. “You won’t even feel it,” they soothed, as if “feeling it”—whatever “it” was—was the source of my fears, which over the course of the pandemic had grown so debilitating that I cried throughout the day, every day, when I thought of my impending death and the deaths of those I loved.

I spoke with Josiah’s father about this. He was an amazing guy, even if we didn’t agree about a lot of religious or political points. It was obvious a lot of his social views had been shaped by common Christian rhetoric—for example, he believed that gay people were sinners, but still treated me with true kindness despite knowing about my sexuality. I respected him more than almost anyone else in my life: he was endlessly compassionate in how he shared his beliefs, and he had built a church that had done real good for the community.

When I told him about my feelings, breaking down crying in front of him as I always did when this topic was broached, he thought about it and told me, with great tenderness and surety, that the intensity of my anguish was an indication of how wrong it was that we all had to die. I tried to take his words to heart, but later I realized that more than dying, what I really feared was having to make a choice—and worrying it would have to be soon. I had heard tales about this, in particular the recollection of Josiah’s mother in a car accident, hearing God’s voice telling her she had to choose Him or die.

I didn’t want to dedicate my life to any God—I wanted to feel in control of my own fate. Yet I was becoming more convinced that perhaps religion was the only way to lead a fulfilling life, to escape oblivion.

Each day I was paralyzed, desperate for deliverance. In English we read 1984 and Frankenstein. Thank God I’d read them both before, so I could flub the reflections and discussions; just thinking about the plots made me depressed.

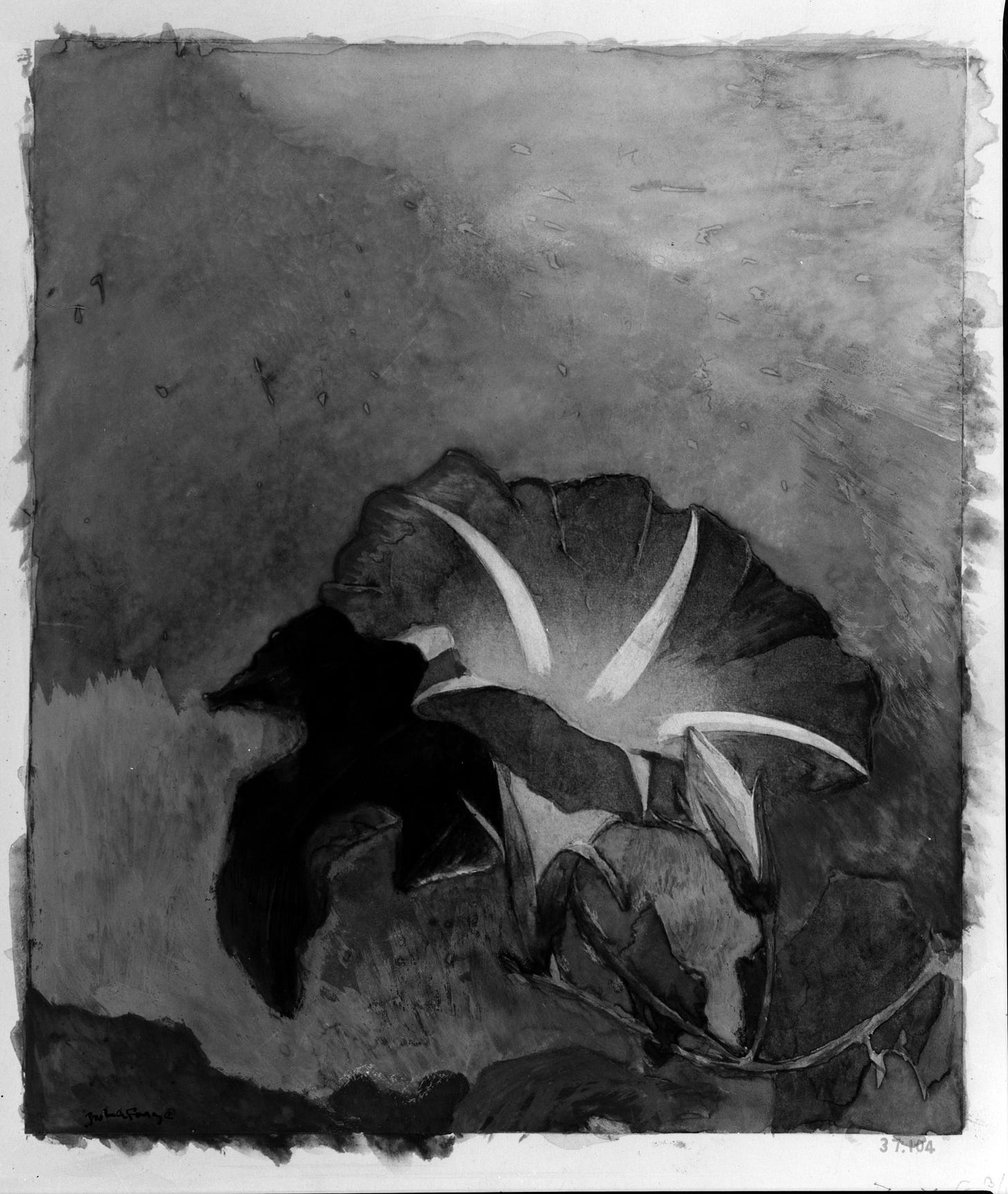

Then we read Siddhartha. (If you haven’t read it, you should, but I will be giving only mild spoilers that won’t affect your enjoyment of the story.) It’s a short novel about a Nepalese man named Siddhartha who lives during the same time as the Buddha and goes on a very long and convoluted spiritual journey to reach nirvana. Wikipedia has a pretty good description of the story’s overall theme:

In Hesse's novel, experience, the totality of conscious events of a human life, is shown as the best way to approach understanding of reality and attain enlightenment—Hesse's crafting of Siddhartha's journey shows that understanding is attained not through intellectual methods, nor through immersing oneself in the carnal pleasures of the world and the accompanying pain of samsara; rather, it is the completeness of these experiences that allows Siddhartha to attain understanding.

In other words, Siddhartha only becomes enlightened after having a set of individual experiences unique to himself and to his path through life. He needed to wander and be lost in order to find what was right for him in the end.

Reading Siddhartha was the only bright spot of the whole academic year for me, and it was the main thing I remember from that spring (apart from the cool community college math class I was taking). Though its message was simple, it somehow was a great reassurance to me—that life really was long, and I really did have time to figure things out, to fuck up and make terrible immoral decisions, and to learn more about myself and the world. When I felt scared I would think about Siddhartha.

When I started college, I felt free: I was sure I’d be able to reinvent myself and to suddenly perform on an equal level with everyone else now that we were all in the same place, with the same resources. It turned out not to be so easy. I spent my first year of college trying to find a community and spent my second year trying to find something I loved to do, and spent the entire time failing over and over.

Each semester I reached a breaking point at least once—each time, I fell behind academically and could not catch back up and had to give something up. I became better and better at doing college, so this point shifted later and later in the semester. The catch is that the closer to finals week this happens, the larger the impact it has on the outcome of the semester, so the consequences of the breakdown also became worse and worse. Finally, I failed quantum mechanics at the end of sophomore spring.

Throughout those first two years of college, I tried to motivate myself by thinking of my future, which had worked out in high school until the pandemic struck. This was because in high school, the portion of my future that I thought about was very straightforward: I would study for my science competitions and try to win them. There was the vague idea that this would prepare me for a career in science afterwards, but mainly I wanted to win the competitions.

During the pandemic this idea of a linear future dissolved as my beloved science competitions morphed into painful Zoom versions of themselves; as I achieved what was nominally my goal for the past four years—to get into a good college—and scrabbled for something to replace it; as my rigid six hours of sleep a night blurred into eight, then ten, then twelve.

And during college this smeared-out vision of the future branched out into an infinite-dimensional space of possibilities, none of which seemed particularly enticing to me as I ran from one commitment to another and spent the time in between feeling about as sentient as a slug. It was death all over again: the death of the narrative I’d clung to for four years; the death of my love for physics, what had ostensibly been my passion for all of high school. Once again, this notion of death—really, of choice, and the terror of being forced to change my path—paralyzed me.

My summer roommate Alex is entering graduate school to research algebraic combinatorics. After watching the first minute of a 3Blue1Brown video in the second week of our internship, they left it on pause for the next three days to work through the problem themselves, talked me through the whole process, and ended up explaining much more than Grant touches on in the video. Their joy was infectious. I didn’t care about combinatorics before they used it to prove this arcane circle theorem and then I felt like combinatorics could be my life and blood.

This happens whenever Alex learns something new. They call me over and tell me all about it and draw diagrams on the back of the Trader Joe’s receipts I leave scattered around our table. Ramsey’s theorem. Symmetry groups and geometry. I grew so used to them telling me all about their math that I started telling them all about my physics. How plasmas release magnetic energy in zaps of reconnection and why Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics and the geometrical intuition behind the definition of e. As I scribbled out Bell’s inequalities in blue fountain pen, told Alex about quantum teleportation and watched their eyes grow bright and wide, I realized how beautiful physics was. It was a feeling I’d forgotten after two years of studying the subject in college, displaced by tedium and frustration.

At my summer internship, almost everyone is older than me, and some people are much older than me—ex-Navy nuclear engineers, students finishing their PhDs with years of work experience already under their belt, guys who have been married for half a decade. They all speak of the future as if it stretches out in front of them limitlessly.

One of the other interns is named Anna and she has legitimately done everything in the world. She trained under a Shaolin monk and built pyrotechnics for Burning Man and learned to ski by being a ski instructor. Somehow, the fact that she’s amazing at everything doesn’t make me feel inferior—instead, I just feel hopeful, like maybe I’ll be as cool as her when I’m her age. A 32-year-old who looks ageless—you’d believe her if she said she was 20 or 40—sitting barefoot on the grass next to me at a Fourth of July celebration, smoking a cigarette (“because I’m physically addicted to it but also because I’ve met so many cool people by asking to borrow lighters”), offering to bring her Muay Thai pads out of her car so we can all learn to box.

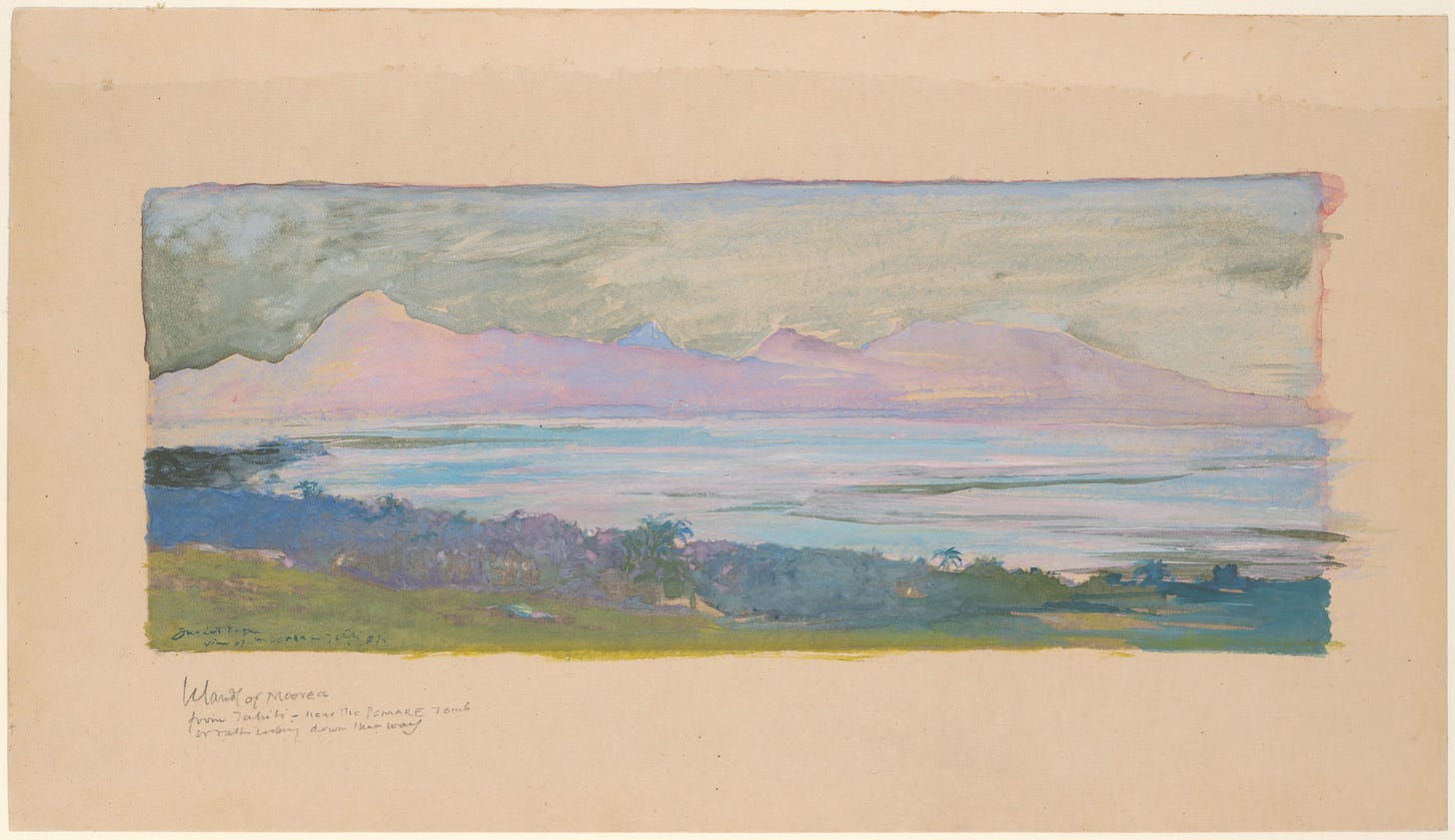

Taken this way, the passage of time becomes less terrifying. This summer has been another Siddhartha to me, an expanding of possibilities laid out onto a canvas that looks beautiful rather than dismal. If I could become like these people who keep reinventing themselves, who keep making choices and altering their stories ten years down the line, it would be foolish to instead remain paralyzed in the face of death.

I am halfway done with college. I turn twenty in less than a month. And Siddhartha, I am still young. Siddhartha, all things will end. Siddhartha, there is so much space between the fire of youth and the stillness of death, and that is where I dwell.

all things end is so good